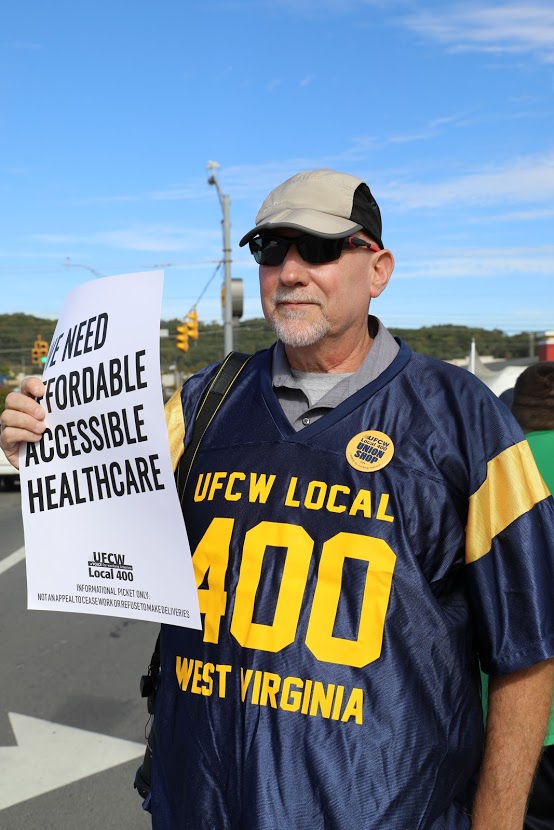

Jim Logan holds a sign at a Kroger rally in West Virginia.

Jim Logan has been a Kroger employee and union member in West Virginia for 42 years. He lives in Caldwell and works in Fairlea, but to people who don’t live there, it’s all Lewisburg – the town with a population of around 3,800 that was named “the coolest small town in America” by Budget Travel in 2011. While Lewisburg may be celebrated for its “breathtaking vistas,” and “eclectic food scene,” the area around it is often overlooked.

“It’s considered a good retirement place, good hunting, good fishing,” Jim says. “You have a wide gamut of people, [you have people] who live at the sporting club at Greenbrier, which is beyond our imagination, and then you have people who are just squeaking by.”

Jim’s coworkers know this better than anyone. “Everyone knows how tight things have gotten in the last ten years,” he says. “And it used to be that it didn’t affect everybody, but no one has any sense of security nowadays.”

But he sees in this economic hardship an opportunity for building solidarity. “Everyone needs to feed a family, and they may differ on certain viewpoints, but beyond that everyone agrees that a livable wage is an important thing, insurance is an important thing,” he says. “We need to focus on those issues and then respect everyone else’s position on different issues, and be willing to allow a diversity of people to come to the table. […] And that’s what the union does in the workplace — it allows people to have a voice in their future. And that’s a precious thing.”

Jim served as a member of the Contract Action Team during negotiations with Kroger last year. “I had really hoped to be at the table negotiating, but instead they put me on the action committee, and I was like, this is not what I want to do,” he admits. “But then I thought, well, if I’m going to be a positive impact, I can’t back down now, I have to do this.”

And he learned a lot in the process, about organizing informational picket lines, connecting with other unions and members from elsewhere, and communicating with customers about workers’ needs.

When the local started organizing demonstrations at Kroger stores throughout West Virginia, Jim and his coworkers were invited to participate at the protest in Beckley, about an hour away. They certainly had cause to demonstrate – turnover was high and only getting higher and many of Jim’s coworkers, especially the younger and newer employees, felt undervalued and disrespected by the company.

Now more than ever, they needed to know that their union was fighting for them and that they could and should participate in that fight. “We just really needed to say, enough is enough,” he says, and they needed to say it in Fairlea.

So they held their own demonstration. “We had a good turnout,” he recalls. “People were coming out on their lunches and breaks and joining in, and it was really well received in the community. [Customers] would literally come up and say, ‘Do you want us not to go in and shop?’ And we would say, ‘No, we just want you to understand what’s going on and what we’re trying to accomplish.”

With mounting public pressure on Kroger, an agreement was reached and a new contract was ratified a few weeks later with zero cuts. This certainly was a victory, but Jim knows there is always more work to be done. And since West Virginia became a right-to-work state in 2016, he’s learning to play a whole new ball game.

“There’s no way someone can just start at a job and grasp all of the dynamics that are involved in having a decent job,” he says. “So [with right-to-work] there’s this huge educational curve, right from the get-go, of what it means to belong to the union and what it can accomplish. And what I’m learning is that in that little 15 minute introduction, without any kind of established relationship with a new person it’s almost an impossible thing to accomplish.”

As an ordained Baptist minister, Jim used to formally pastor a church, but since he’s lived in Caldwell, West Virginia he’s been “unchurching,” or holding services in people’s houses. On Tuesday nights he hosts bible study in his own home, and every once in a while, he hosts a union meeting. Otherwise, Jim and his co-workers have to drive an hour to get to union meetings, which he says can be economically burdensome.

He usually only hosts union meetings at his house for special occasions, but he’s been thinking about hosting more casual get-togethers, “bridge-builders” he calls them, to help create a stronger sense of community in his store.

“It’s probably the direction we need to go,” he says. “Now in an environment of right-to-work, you’ve got those issues of trust and truth again. You can say you care but sometimes you have to show you care.”

With 42 years of experience under his belt, Jim Logan sounds patient, almost calm, but part of what allows him to connect with younger workers is that he remembers how frustrating it was to be in their position.

He has a saying: “A bunch of straws are harder to break than just one.” He knows that all of his co-workers complaints are valid, no matter how long they’ve been working for Kroger, but he also knows that the best way to address them is to stand together.

“I try to articulate it’s a long-term investment,” Jim says about union dues. “And when [new employees] look in that contract they can see some of those better wages, [and realize] that it took everyone a long time to get there but the only way to get there is to stick together.”

Both his patience and his passion are manifestations of how much Jim Logan cares. He says he doesn’t know why he became a shop steward. But then he says, with absolute certainty, “I really care about people. And I’ve got this thing, if someone is an underdog or at a disadvantage, if someone takes advantage of that, that just really lights me up. It’s something in my nature.”

And it’s not changing any time soon. As he looks forward, Jim has a bunch of ideas for how he can better support his fellow union members and build community relationships, both in his corner of West Virginia and throughout the region. He hopes to retire from Kroger soon, but not from union activism.

“If and when I get to retire, I think that then I will become more and more politically active, because the union needs friends,” he says. “And I will do it without compromising, because I’m not doing it for a career or economics, just because it’s the right thing to do.”